About a month ago I was working with a team planning another iteration for the project, when we had an interesting discussion about how to manage our burndown.

On all of our previous sprints, our burndowns were based on hours. That is, for each day of the sprint, team members would revise their estimates of the time left for any tasks they were working on. Typically (though not always), this means they were revising their estimates downward, and so the curve trends downward over the course of the sprint. At the end of the sprint, it ideally reaches zero on the last day as all the tasks are completed.

On the projects for that particular company we have traditionally always burned down by hours. What I like about that is you get a real sense of it things are going astray. Because you often end up revising estimates upward early in a sprint, it’s a way to show that as you started to dive into tasks, things turned out to be more complicated than you expected. If that’s only happening on a few tasks, it’s not a big deal and while your burndown may initially be a little flat, the iteration is still probably not in jeopardy and you can usually recover.

But if the burndown takes a significant jump up, perhaps because lots of tasks are taking longer than expected, then you know you have a serious problem that needs to be addressed. Burning down hours makes it easier to a team to raise this red flag, in a way that burning points down does not.

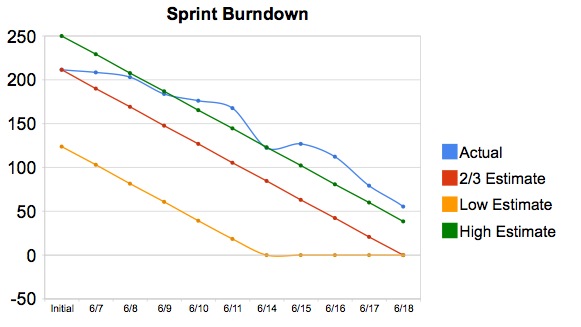

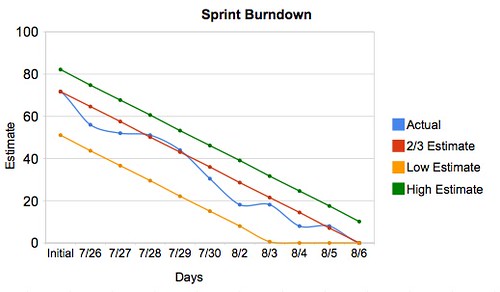

The other thing that I like about burning down by hours is that it provides an easy way for the team to estimate in ranges. As I’ve indicated in many other posts and in talks I’ve done at conferences, I love estimating in ranges (ie, 4-8 hours), instead of in single points (ie, 5 hours). Range estimation allows me to more accurately communicate the risk and uncertainty of a task. A wide range indicates larger risk and uncertainty than a narrow range.

When I make my initial estimates for an iteration in ranges, then I can put some nice boundaries around my burndown, as I’ve also discussed in other posts.

However, there is also a good case to be made for burning down in points. In this recent project, one team member had joined from another company and he made the case for burning down in points. His preference was based in part because burning down by hours can always be “gamed”, ie, you can remove tasks from the iteration or just give misleading estimates in order to make the burndown look better. Furthermore, burning down by story points gives a clear indication of what is truly done, and at what point in an iteration the story is complete. By doing so, you keep the team more focused on what is truly done, and less focused on the way you got there (ie, the tasks estimates). No less than Jeff Sutherland, co-creator of Scrum has stated that “The best teams I work with burn down story points. They only burn down when a story is done.”

The rest of the team expressed some hesitation about going this route. In part because we liked the use of ranges and felt that it forced us to be more conservative in the stories and tasks we take on in a sprint. And in part because we felt the burndown would communicate less because most stories would not end up being done until the very end of the iteration.

However, our fears that no stories would get marked done until near the end of the sprint may have been symptomatic of another problem: our stories were simply too big. Jeff Sutherland notes in his blog post that “to do this, the team needs to have small stories.” If the story is not small enough for each developer to have multiple stories during the sprint, then burning down by points may not work well. I’ve heard Mike Cohn say that on average each developer should have 2-3 stories in an iteration, and I would say that is the minimum needed to make this approach work. I wonder if a slightly smaller breakdown so that everyone has 4-5 stories would probably work even better.

Both approaches have a lot of merit to them however, and so why not do both? I realized this was an option when I attended an Agile Richmond talk recently, given by Guy Beaver, co-author of “Lean Agile Software Development”

Guy described using both charts on the same projects, in what he called an “Agile V” burndown configuration. Basically you put a burndown of hours on the left, and a burnup of story points on the right. Ideally as your hours burndown goes to zero and your points burnup goes to 100% complete, you get a rough V shape at the end. Some teams have even superimposed the two charts on one plot (using both an hours and points scale on the y-axis), to get an “Agile X” shape in their burndowns/burnups.

Image from this post by Guy Beaver on Agile Journal

You can see a post from Guy on this topic here, where he describes how this approach results in an “Agile-V Scorecard.” I particularly like how he describes that this approach has benefits for a new team to help them keep focus on delivering value. He also describes how for a mature team, this approach allows them to realize early in an iteration when enough stories aren’t being delivered (you should be able to knock out a couple early in the sprint), and therefore some obstacles must exist that need to be removed.

I like this idea, since it combines the best of both worlds. As long as you are not adding a lot of overhead in asking developers to both re-estimate their hours remaining on a daily basis, as well as track when a story is “done”, then it seems like a good path to try. If you combine it with my range estimation techniques on the burndown, then you are getting the benefit of the conservative estimation techniques, as well as the “focus on completion” of the burnup. Those are mutually beneficial strategies to follow.

There are even additional benefits that such a combined approach may encourage. As one commenter on this forum post notes, “with this combination you can detect multi-tasking.” If the burndown of hours is progressing fine, but no completed stories are reflected on the story point burnup, then the team may be multitasking between stories too much. So having both charts will encourage the team to follow good lean and kanban practices of limiting the work in progress, and just getting things done.

In this particular project I mentioned at the beginning, after some discussion we ultimately decided to stick with the hours burndown rather than switch to the points burndown. Only one team member wanted the switch, and we were reluctant to change directions mid-project. But it was a good discussion and it got me thinking about how to address both sets of valid concerns.

After hearing Guy’s talk and doing more research, I think the next time I’m in that situation I will not allow it to be a choice of one or the other. Doing both may offer significant benefits and I’m curious to try it out.